WHEN Mae West, Hollywood’s queen of the double entendre, arrived at the country house hotel managed by Sandy Johnson’s father, alongside Loch Lomond and the rugged Ben Lomond, legend holds she huskily lisped: “Who is this Ben Lomond? Mmm, sounds like a big guy!”

Given that the hotel was a favourite amongst the show business elite including Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh among its guests, there’s a case that perhaps different kinds of stars did align to guide him along a top tier career as a film and TV director.

As a director he appears to have been an A list player practically from the start of his career, shaping performances from the proverbial A-Z of the UK acting elite, plus a few from abroad such as Isaac Hayes, Jo Don Baker and Star Trek’s William Shatner.

Again, his TV credits read like the Premier League of British comedy drama rewarded with a clutch of BAFTAs. His shows include: The Comic Strip Presents, Inspector Morse, The Ruth Rendell Mysteries, Jonathan Creek, A Touch of Frost, Auf Wiedersehn Pet, Harry and Paul (as in Enfield and Whitehouse), Professor Branestawm, Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years, Benidorm, Death in Paradise, and its current BBC1 spin-off Beyond Paradise (cast right).

Again, his TV credits read like the Premier League of British comedy drama rewarded with a clutch of BAFTAs. His shows include: The Comic Strip Presents, Inspector Morse, The Ruth Rendell Mysteries, Jonathan Creek, A Touch of Frost, Auf Wiedersehn Pet, Harry and Paul (as in Enfield and Whitehouse), Professor Branestawm, Adrian Mole: The Cappuccino Years, Benidorm, Death in Paradise, and its current BBC1 spin-off Beyond Paradise (cast right).

Ettinger Brothers Productions are delighted to be working with him to develop a new series of film and TV projects across a varied range of subjects which will benefit from his immense experience and talent.

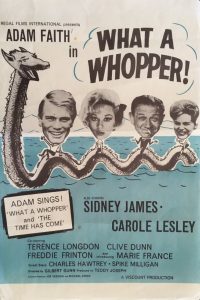

As a toddler Sandy met Hollywood heart-throb Tyrone Power, and vaguely recalls British film star Richard Todd while filming a Disney production (whose Irish wolfhounds were taller than him), but very much more remembers Adam Faith who was filming What A Whopper (about the Loch Ness monster – what else?).

As a toddler Sandy met Hollywood heart-throb Tyrone Power, and vaguely recalls British film star Richard Todd while filming a Disney production (whose Irish wolfhounds were taller than him), but very much more remembers Adam Faith who was filming What A Whopper (about the Loch Ness monster – what else?).

“I don’t know if this influenced my career choice, as my father died when I was four and my mother came out of the hotel trade, he says. “I was especially proud of my cardboard cinema using a Chad Valley projector for cartoons which I loved. I’ve always been into audio-visual things from an early age. I was always interested in making model theatres and puppets.

“We’ve no show business connections apart from my mother Margaret (who was a keen photographer), knowing the famous actress Dame Anna Neagle very well and kept her photo in her bedroom.”

Like many successful creative people, Sandy had an early inspirational mentor in the form of his art teacher at Glasgow High School and says, “He was really into films and collected Laurel and Hardy 16mm prints. There was always the sound of old 78 records drifting out of the art room.

“He had a 9.5mm and a 16mm camera which we used to make two films, a silent Roman epic called The Great Truss and a subversive one called It’s a Disgrace, lampooning school traditions with the Headmaster’s favourite cry as a title!

“The Art Department was a refuge for me from rugby, cricket and other sports. We watched art films and mainstream works like The Trials of Oscar Wilde, starring Peter Finch, and he took us to see Fellini’s Satyricon.![]()

“In our village we didn’t have a cinema but monthly films in a hall were shown on a 16mm projector. Watching Blake Edwards’ The Great Race there knocked me out. There was something about comedy and its techniques that I was always into. To this day I still think, what would Blake Edwards do in this scene?”

“Of course, there were the Sunday afternoon films on TV from the 1930s and ‘40s, plus Buster Keaton silents and all that stuff, which I loved along with ‘film noir’ and the brilliant comedies of Preston Sturges like Sullivan’s Travels.”

As a very keen teenage actor, he joined the Buchanan Dramatic Society and performed plays like Waiting for Godot at high school and as a result almost went to drama school, but instead chose Glasgow Art School to pursue drawing and painting. His magnetic attraction to famous names continued as he was lucky enough to meet David Hockney during Activities Week.

While at art school he acted with the Strathclyde Theatre Group’s semi-pro shows and Edinburgh Festival productions and drifted away from film making (as he had no camera until he found a Bolex 16mm camera at the art school).

productions and drifted away from film making (as he had no camera until he found a Bolex 16mm camera at the art school).

Sandy was saved from unrequited attempts to get corporate work when an aunt left him a £200 legacy: “I blew it all on FP4 B/W film and made a short called Timepiece about a Victorian hermit who goes into the outside world, finds himself in 1970s Glasgow and eventually goes mad.”

After Colin Young, founding director of the National Film & Television School, saw the film he was encouraged to apply. Other alumni from his intake included future directors Bill Forsyth (Gregory’s Girl and Local Hero) and Mike Radford (Nineteen Eighty-Four and White Mischief) and Julian Temple (Absolute Beginners).

“At art school I continued acting and heard word that Monty Python was holding auditions for its Holy Grail film to be made around Stirling. I got five various parts including a Knight Who Says Ni, right, a villager at the witch burning, a wedding musician, and monk.

“At art school I continued acting and heard word that Monty Python was holding auditions for its Holy Grail film to be made around Stirling. I got five various parts including a Knight Who Says Ni, right, a villager at the witch burning, a wedding musician, and monk.

“It was a very enjoyable experience, like being part of a big family. I met all of the Pythons, who were very friendly. This was my first experience of a film unit and I was very impressed. They seemed to make a virtue of the fact it was made on a shoestring and had nothing, yet it felt like a big movie with a fantastic quality – things like costumes by the renowned Hazel Pethig, and make-up.

“Then bizarrely, while I was in London to be interviewed for film school, I visited Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese pub, in Fleet Street, and went to the gents. The middle stall of the urinal was free and I realised the two men either side of me were the Pythons Michael Palin and Terry Jones.

“They recognised me and asked what I was doing in London. Michael Palin said, ‘Do you want to come and see the first screening of The Holy Grail on Friday?’ which was at a private studio in Wardour Street.

Ignoring such a serendipitous invitation was unthinkable and he recalls: “It was fantastic as we were all seeing the film for the first time. At the end, when the lights went up the assistant director Jerry Harrison shouted out, ‘Well done Sandy!’ to embarrass me in front of somewhat more important people like the Pythons themselves. . .”

On the other hand, you can’t help but feel once again that the notoriously fickle finger of show business fate made a very early bid to put Sandy, a humble Stirling village witch burning player, centre stage in front of these internationally acclaimed comedians. In fact he was later to go on and direct another famous Python, John Cleese, in Hold the Sunset, a 2018 BBC situation comedy series with Alison Steadman, left. All thanks to a fortuitous visit to the toilet.

On the other hand, you can’t help but feel once again that the notoriously fickle finger of show business fate made a very early bid to put Sandy, a humble Stirling village witch burning player, centre stage in front of these internationally acclaimed comedians. In fact he was later to go on and direct another famous Python, John Cleese, in Hold the Sunset, a 2018 BBC situation comedy series with Alison Steadman, left. All thanks to a fortuitous visit to the toilet.