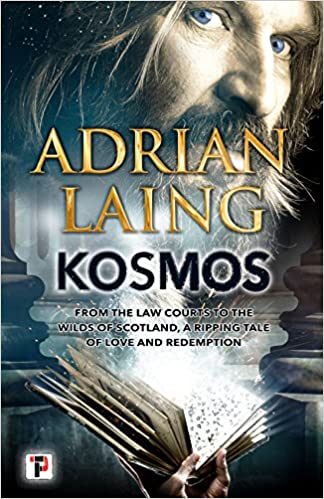

Taking his sons on the daily school run in north London, Adrian Laing passed Boudicca’s Mound, on Hampstead Heath, where the legendary Iceni queen was once thought to be buried, and this created the germ of an idea, which became his novel Kosmos.

“I had this fantasy that someone would be found there, but they don’t know who they are. Does the character think they are, say, Jesus Christ? But that would be too controversial for what I wanted to write,” says Adrian Laing.

“But it would be acceptable for the sake of the story if the character really thinks he is the wizard Merlin, as the King Arthur mythology fascinate me. How do your other characters disprove this?

“I also wanted to write a fictionalised account of what it was like to be a pupil barrister. The Merlin character is an old lag, represented by my lead character George Winsome to capture the essence of what it’s like to be a young barrister. Then I added the relationship with his fellow pupils, as I wanted to show what the camaraderie is like among young lawyers.”

But there is also a darker aspect to a pupil barrister’s work: “Suddenly you’re in court representing people, which can be absolutely brutal. You’re given a brief and told to get on with it.

“By osmosis you hopefully become a calm, professional advocate, but I know people whose careers ended on day one. I wanted to capture that transition into a hardened courtroom lawyer for George in Kosmos.

“The story all comes together in a three-way junction of a love story, the trials and tribulations of a pupil barrister, all wrapped around the enigma of an old boy who thinks he’s Merlin.”

This structure allowed Adrian Laing to cover many issues he felt were important through a collection of different dynamics, including a set-piece dramatized courtroom trial.

“Coincidentally, while I was writing the jury deliberation’s scene, I was summoned to jury service and it gave me first-hand experience of the process of reaching a decision through the conflicts between a group of people. I was so shocked at the frailty of justice. It’s only as just as the people who administer it.”

Obviously, this revelation is all in the service of an entertaining novel, not as a thinly veiled biography or about the shortcomings of the law.

“The best writers are those with a lack of inhibition about being creative,” he believes. “The legal thriller writer John Grisham is a very rare talent to have this creativity. His novels involve sharp legal procedure, but above all are driven by his imagination.

“Another example is Nigel Tranter, who died about 20 years ago. He wrote huge amounts of literature about Robert the Bruce, and I learnt a lot being fed history of the 1300s through his dramatizations.

“Bernard Cornwell wrote his Napoleonic war series of Sharpe novels to warm up before tackling Anglo-Saxon historical fiction. They had a very good preface which followed the history as much as possible up to a point and this provided a strong foundation. I met Bernard Cornwall and must admit enjoyed winding him up until my boss made a diplomatic intervention.

Adrian Laing cites the trio of novels Don Quixote, Moby Dick and Gulliver’s Travels as among the top examples of “incredible feats of uninhibited imagination”, whose authors effortlessly shift time, characters and events.

“You get the sense the author has no idea where he’s going to the big ending, but it’s fun being on the ride with him. I spent a morning in a Waterstones bookshop reading the first five pages of as many novels as possible to learn how to get into a story.

“By far the best is Charles Dickens. Suddenly you’re in a totally different world. This is done so subtly and skilfully that for the first two or three pages the reader hasn’t even noticed.”

In case you wondered, Adrian Laing admits writing a novel is a big challenge, with the solitary, lonely task of facing a blank sheet of paper. Besides Kosmos, published in 2018, he also penned Rehab Blues, about a Priory-style centre for celebrity burn-out, in 2013.

Having written many legal articles and books, including most recently the Bluffer’s Guide to Law he understood the discipline of structure, the framework of chapters, word counts and popular subject areas.

He says: “It’s like building a house, you do it in stages; it was never that difficult to get published as a legal writer and deals to write books on law, co-authored with his barrister wife Deborah Fosbrook, was a natural progression.

“However, I was always determined to write a novel and soon realised it was a very particular process. Even at primary school I was told I had a creative mind but writing your first novel is like running an endless marathon. Blindfold.

“A novel requires a plot, and you don’t want to spoil the book by giving away the end too soon. You’ve got to write whatever is in your mind in your own way -and hopefully you get better as you do it!”